Why do some metals not expand when heated?

Crystal structure with overlaid snapshots of atomic positions representing the vibrational motion around their equilibrium positions. Heat (thermal energy) induces those vibrations, which cause distortions of the structure. Larger temperatures cause larger thermal vibrations and usually result in a volumetric expansion of the lattice.

In 1895, Swiss physicist Charles Édouard Guillaume discovered that melting two cheap and abundant metals together, iron and nickel, resulted in an alloy that does not expand when heated. The volume invariance of this material with temperature earned the name invar effect. While this might not seem like the most thrilling scientific discovery, such properties are invaluable in engineered devices that require structural stability against temperature changes. Have you seen photos of train tracks dramatically buckling in the heat because of their expansion? Invar alloys are used in everything from large pipelines and tanks to precision instruments such as microscopes, telescopes, and orbiting satellites. Temperature variations also undermine the precision of timekeeping, since the properties of springs inside watches are affected by heat. The discovery of the invar effect revolutionized the watch industry.

Guillaume himself cleverly publicized the invar effect to both Parisians and the academic world using none other than the newly constructed Eiffel Tower. He hung a long invar wire from the second platform down to the ground, 135 meters below, to measure the tower's expansion as temperatures fluctuated over several days. Since the invar wire remained unchanged, it served as a precise length reference to detect small variations of about 2 centimeters. The technical significance of invar, and perhaps Guillaume’s sharp publicity skills, culminated in his 1920 Nobel Prize in Physics. Because of Guillaume, Albert Einstein had to wait another year for his own Nobel, which was awarded in 1921.

Minimizing thermal expansion is technically useful, but the invar effect also raises a puzzling scientific question: How does an alloy of two metals, both of which have substantial thermal expansion, result in a material that does not expand at all? This mystery led to thousands of scientific studies, shedding light on electronic and magnetic aspects that gave pieces of the answer. Guillaume himself suspected that magnetism played a role, as the effect vanished when the metal was heated above its magnetization regime.

Most materials expand when heated. Think of a hot air balloon, or the next time you drive over a bridge, notice the small gaps at both ends designed to accommodate the expansion. But why do materials expand? Simply put, higher temperatures cause atoms to vibrate more intensely, typically requiring more space. These atomic vibrations, known as phonons in quantum mechanics, account for most of a material’s thermodynamic behavior.

However, invar is also ferromagnetic. In ferromagnetic materials, the small magnetic fields created by spinning electrons are all aligned, resulting in a net macroscopic magnetization. Thermal energy excites not only atomic vibrations but also these electronic spins, which become increasingly disordered as temperature rises. This loss of magnetization has volumetric effects. To qualitatively understand this, we can rely on Pauli’s exclusion principle: Two interacting electrons cannot occupy the same energetic state. So the electronic orbitals of neighboring atoms cannot overlap if all spins are aligned. But as magnetic order relaxes with increasing temperature, this restriction also weakens, allowing atoms to move closer together and causing the material to contract.

This leads to the question: Can this magnetic contraction counteract the thermal expansion caused by atomic vibrations, effectively canceling out expansion altogether? Can these two contributions, magnetic and vibrational, be measured independently to resolve this long-standing question? Or is there another missing piece to the puzzle?

As an experimental scientist, this sounds like an exciting challenge. A fundamental open question in materials science that required experimental proof was right up my alley. But I also understood why it hadn’t been done before. The volume expansion is a bulk property, and individual atomic-scale contributions cannot be directly measured. There’s no such thing as a separate "magnetic" or "vibrational" volume that can be observed.

This is where James Clerk Maxwell—or rather, the set of thermodynamic relations that bear his name—comes into play. One of these relations states that the change in volume with temperature (thermal expansion) is equal to the change in entropy with pressure. Think of this as a change of coordinates: if we shift our perspective and control pressure instead of temperature, entropy rather than volume becomes the key variable. Entropy is a fundamental thermodynamic quantity that reflects how energy is distributed among the microscopic states of a system and, importantly, it allows us to distinguish between the vibrational and magnetic contributions to thermal expansion. Entropy increases with the level of microscopic disorder. Large atomic displacements correspond to high vibrational disorder and entropy, while the loss of spin alignment represents an increase in disorder and greater magnetic entropy.

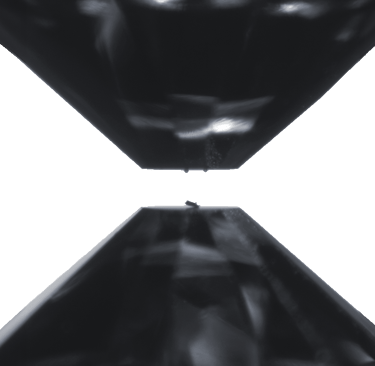

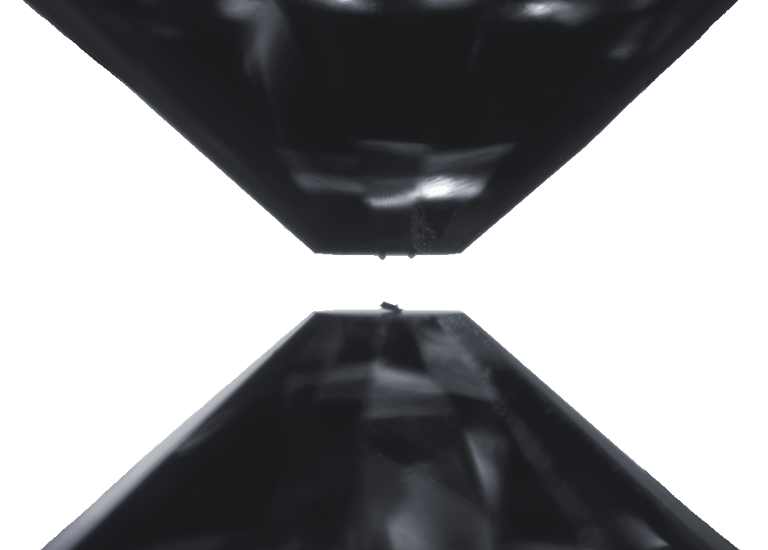

Measuring these individual contributions is no small feat. Probing the vibrational spectrum of a material, for example, requires large particle accelerators. Controlling pressure is also significantly more challenging than simply heating a sample. It took me weeks to learn how to load samples into a diamond-anvil cell to achieve high pressures. It involved many frustrating days of staring through a microscope, trying to manipulate a sample smaller than a human hair using nothing more than a needle and a pair of tweezers. My dexterity, the fruit of years of random creative and crafting endeavors, paid off: I had an invar sample squeezed in between the tip of two opposing diamond anvils.

My experimental investigation of a long-standing open question in materials science.

Electronic spins of individual atoms and the local magnetic fields they create (represented by arrows). In ferromagnetic materials, the spins are aligned at low temperatures (left), contributing to a net macroscopic magnetization. Thermal energy disrupts the spin alignment, and above the Curie temperature (right), the magnetization is lost. This magnetic disorder causes a contraction of the structure.

Stefan Lohaus, Postdoctoral Scholar at the California Institute of Technology.

After submitting an experimental proposal and waiting through the review process, I gained access to the Advanced Photon Source, a synchrotron that produces ultra-bright X-rays at Argonne National Laboratory near Chicago.

I may be biased, but our experimental setup was beautiful. Three detectors, positioned close to the sample, measured the energy exchanged between X-rays and atomic vibrations using a technique called nuclear resonant inelastic X-ray scattering. At the same time, another detector, sensitive to time-dependent changes in the X-rays interacting with magnetic spins, measured the material's local magnetization. With these two complementary techniques, we could independently track both contributions to the entropy, magnetic and vibrational, and thus, the individual pieces of the thermal expansion.

After a long and careful analysis of the data, we finally had our answer: atomic vibrations cause a substantial thermal expansion, but in invar materials, it is precisely canceled by a lattice contraction due to magnetic disordering. Beyond experimentally confirming this elegant thermodynamic explanation of the invar effect, we also discovered that vibrational and magnetic excitations are not independent. Instead, electronic spins exchange energy with atomic vibrations, which enhances the cancellation between vibrational expansion and magnetic contraction over a wider range of pressures.

This story highlights the power of studying microscopic interactions to explain macroscopic behaviors—the essence of materials science. What physical form does thermal energy take, and what atomic-scale excitations absorb that energy? The concept of entropy is the bridge between microscopic dynamics and macroscopic physical properties. And by deconstructing entropy into its vibrational and magnetic components, we were able to observe what is behind invar’s anomalous behavior. Based on what we learned from the invar effect, we could think of tailoring the amount of thermal expansion and other thermophysical properties, such as elasticity modulus, by strategically engineering their microscopic vibrational and magnetic behavior.

Two opposing diamonds in a diamond-anvil cell. The flat tips, called culets, are 0.3 mm across (approximately 1/100 inches). The invar sample, placed in the bottom culet, is about the width of a human hair. The two spheres on the top anvil are Ruby spheres used as reference material to monitor the pressure. Before pressuring, a metallic gasket is placed between the culets around the sample, trapping an inert gas that serves to create an isotropic (homogeneous) pressure environment at the sample.

March 4, 2025.

Why do some metals not expand when heated?

Crystal structure with overlaid snapshots of atomic positions representing the vibrational motion around their equilibrium positions. Heat (thermal energy) induces those vibrations, which cause distortions of the structure. Larger temperatures (right figure) cause larger thermal vibrations and usually result in a volumetric expansion of the lattice.

In 1895, Swiss physicist Charles Édouard Guillaume discovered that melting two cheap and abundant metals together, iron and nickel, resulted in an alloy that does not expand when heated. The volume invariance of this material with temperature earned the name invar effect. While this might not seem like the most thrilling scientific discovery, such properties are invaluable in engineered devices that require structural stability against temperature changes. Have you seen photos of train tracks dramatically buckling in the heat because of their expansion? Invar alloys are used in everything from large pipelines and tanks to precision instruments such as microscopes, telescopes, and orbiting satellites. Temperature variations also undermine the precision of timekeeping, since the properties of springs inside watches are affected by heat. The discovery of the invar effect revolutionized the watch industry.

Guillaume himself cleverly publicized the invar effect to both Parisians and the academic world using none other than the newly constructed Eiffel Tower. He hung a long invar wire from the second platform down to the ground, 135 meters below, to measure the tower's expansion as temperatures fluctuated over several days. Since the invar wire remained unchanged, it served as a precise length reference to detect small variations of about 2 centimeters. The technical significance of invar, and perhaps Guillaume’s sharp publicity skills, culminated in his 1920 Nobel Prize in Physics. Because of Guillaume, Albert Einstein had to wait another year for his own Nobel, which was awarded in 1921.

Minimizing thermal expansion is technically useful, but the invar effect also raises a puzzling scientific question: How does an alloy of two metals, both of which have substantial thermal expansion, result in a material that does not expand at all? This mystery led to thousands of scientific studies, shedding light on electronic and magnetic aspects that gave pieces of the answer. Guillaume himself suspected that magnetism played a role, as the effect vanished when the metal was heated above its magnetization regime.

Most materials expand when heated. Think of a hot air balloon, or the next time you drive over a bridge, notice the small gaps at both ends designed to accommodate the expansion. But why do materials expand? Simply put, higher temperatures cause atoms to vibrate more intensely, typically requiring more space. These atomic vibrations, known as phonons in quantum mechanics, account for most of a material’s thermodynamic behavior.

This leads to the question: Can this magnetic contraction counteract the thermal expansion caused by atomic vibrations, effectively canceling out expansion altogether? Can these two contributions, magnetic and vibrational, be measured independently to resolve this long-standing question? Or is there another missing piece to the puzzle?

As an experimental scientist, this sounds like an exciting challenge. A fundamental open question in materials science that required experimental proof was right up my alley. But I also understood why it hadn’t been done before. The volume expansion is a bulk property, and individual atomic-scale contributions cannot be directly measured. There’s no such thing as a separate "magnetic" or "vibrational" volume that can be observed.

This is where James Clerk Maxwell—or rather, the set of thermodynamic relations that bear his name—comes into play. One of these relations states that the change in volume with temperature (thermal expansion) is equal to the change in entropy with pressure. Think of this as a change of coordinates: if we shift our perspective and control pressure instead of temperature, entropy rather than volume becomes the key variable. Entropy is a fundamental thermodynamic quantity that reflects how energy is distributed among the microscopic states of a system and, importantly, it allows us to distinguish between the vibrational and magnetic contributions to thermal expansion. Entropy increases with the level of microscopic disorder. Large atomic displacements correspond to high vibrational disorder and entropy, while the loss of spin alignment represents an increase in disorder and greater magnetic entropy.

Measuring these individual contributions is no small feat. Probing the vibrational spectrum of a material, for example, requires large particle accelerators. Controlling pressure is also significantly more challenging than simply heating a sample. It took me weeks to learn how to load samples into a diamond-anvil cell to achieve high pressures. It involved many frustrating days of staring through a microscope, trying to manipulate a sample smaller than a human hair using nothing more than a needle and a pair of tweezers. My dexterity, the fruit of years of random creative and crafting endeavors, paid off: I had an invar sample squeezed in between the tip of two opposing diamond anvils.

However, invar is also ferromagnetic. In ferromagnetic materials, the small magnetic fields created by spinning electrons are all aligned, resulting in a net macroscopic magnetization. Thermal energy excites not only atomic vibrations but also these electronic spins, which become increasingly disordered as temperature rises. This loss of magnetization has volumetric effects. To qualitatively understand this, we can rely on Pauli’s exclusion principle: Two interacting electrons cannot occupy the same energetic state. So the electronic orbitals of neighboring atoms cannot overlap if all spins are aligned. But as magnetic order relaxes with increasing temperature, this restriction also weakens, allowing atoms to move closer together and causing the material to contract.

My experimental investigation of a long-standing open question in materials science.

Electronic spins of individual atoms and the local magnetic fields they create (represented by arrows). In ferromagnetic materials, the spins are aligned at low temperatures (left), contributing to a net macroscopic magnetization. Thermal energy disrupts the spin alignment, and above the Curie temperature (right), the magnetization is lost. This magnetic disorder causes a contraction of the structure.

Stefan Lohaus, Postdoctoral Scholar at the California Institute of Technology.

After submitting an experimental proposal and waiting through the review process, I gained access to the Advanced Photon Source, a synchrotron that produces ultra-bright X-rays at Argonne National Laboratory near Chicago.

I may be biased, but our experimental setup was beautiful. Three detectors, positioned close to the sample, measured the energy exchanged between X-rays and atomic vibrations using a technique called nuclear resonant inelastic X-ray scattering. At the same time, another detector, sensitive to time-dependent changes in the X-rays interacting with magnetic spins, measured the material's local magnetization. With these two complementary techniques, we could independently track both contributions to the entropy, magnetic and vibrational, and thus, the individual pieces of the thermal expansion.

After a long and careful analysis of the data, we finally had our answer: atomic vibrations cause a substantial thermal expansion, but in invar materials, it is precisely canceled by a lattice contraction due to magnetic disordering. Beyond experimentally confirming this elegant thermodynamic explanation of the invar effect, we also discovered that vibrational and magnetic excitations are not independent. Instead, electronic spins exchange energy with atomic vibrations, which enhances the cancellation between vibrational expansion and magnetic contraction over a wider range of pressures.

This story highlights the power of studying microscopic interactions to explain macroscopic behaviors—the essence of materials science. What physical form does thermal energy take, and what atomic-scale excitations absorb that energy? The concept of entropy is the bridge between microscopic dynamics and macroscopic physical properties. And by deconstructing entropy into its vibrational and magnetic components, we were able to observe what is behind invar’s anomalous behavior. Based on what we learned from the invar effect, we could think of tailoring the amount of thermal expansion and other thermophysical properties, such as elasticity modulus, by strategically engineering their microscopic vibrational and magnetic behavior.

Two opposing diamonds in a diamond-anvil cell. The flat tips, called culets, are 0.3 mm across (approximately 1/100 inches). The invar sample, placed in the bottom culet, is about the width of a human hair. The two spheres on the top anvil are Ruby spheres used as reference material to monitor the pressure. Before pressuring, a metallic gasket is placed between the culets around the sample, trapping an inert gas that serves to create an isotropic (homogeneous) pressure environment at the sample.